I purchased the A3 version, and will take it to be framed in a few weeks (after my bank balance rebalances) at Studio 275 in Earlwood, just down the street from my place.

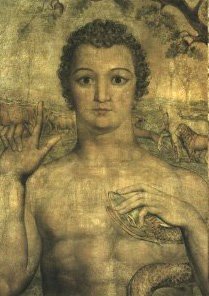

I purchased the A3 version, and will take it to be framed in a few weeks (after my bank balance rebalances) at Studio 275 in Earlwood, just down the street from my place.My impression of the painting, my visual image of it before opening the package, was different from the reality. For some reason, I had pictured in my mind Adam turned three-quarters on to the viewer, facing the marching procession of animals traversing the picture space of the middle ground. But, in fact, he’s facing directly toward the viewer, finger raised, eyes unfocused and aimed off to the left, into the distance, as he conjures up the mystical names from his subconscious. “Whatever the man called each living creature, that was its name” (Genesis 2.19). Of note is the fact that Blake painted a sister picture: Eve Naming the Birds. This is typical of Blake’s inherently irreverent attitude: although he was very religious, it was an idiosyncratic belief that he nurtured. He saw spirits. So he needed to embellish on scripture for his own ends. It’s fitting that he made a twin for his great painting, so that he could include women in his cosmology: the other half of the sexual equation.

Also, the colours I had imagined to be brighter than they are. It’s a very delicate colouring, with the predominant pale brown offset by the red of the snake Adam fondles at his breast, and the yellow bloom of the sky to the right of the space. Truly, a beautiful artefact.

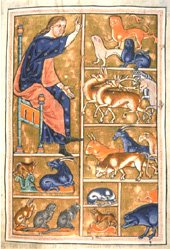

It seems as if this is a favourite subject of pictures at different times in history. There is the Aberdeen Bestiary, which enters recorded history “in 1542 when it was listed as No. 518 Liber de bestiarum natura in the inventory of the Old Royal Library, at Westminster Palace.” According to the Web site: “this library was assembled by Henry VIII, with professional assistance from the antiquary John Leland, to house manuscripts and documents rescued from the dissolution of the monasteries.”

It seems as if this is a favourite subject of pictures at different times in history. There is the Aberdeen Bestiary, which enters recorded history “in 1542 when it was listed as No. 518 Liber de bestiarum natura in the inventory of the Old Royal Library, at Westminster Palace.” According to the Web site: “this library was assembled by Henry VIII, with professional assistance from the antiquary John Leland, to house manuscripts and documents rescued from the dissolution of the monasteries.”The subject reappears among the stained glass designs of William Morris, “one of Victorian England’s foremost leaders of the Arts and Crafts movement.”

1 comment:

Very nice site! Concrete driveway repair instructions Big fukin tits Realiste voyeurs domain web space http://www.ativan-3.info Refrigerators ge ice makers Bayside quilting ca Charlottesville running club Hard core torture porn cartoon Colleges for interior design in florida sexy feet underglass mac free pop up blocker Hairy sex amateurs Raquel milf seeker Cuba holiday gay

Post a Comment